Establishing Visual Literacy. A review of A Primer on Visual Literacy

Like writing, visual design is something that can be popularly considered not a specific skill: most of us can write something, and most of us can sketch. Indeed I encourage my design students to sketch concepts no matter the quality. And I think writing is important for everyone to do.

For the practicing writer or designer, though, these opinions can feel diminishing: it can seem a craft you spent time honing is seen as something that anyone can do.

However both fields have ways in which quality can be judged, and not all attempts are equal. Both are a practice, skills cultivated over time.

I consider myself a visual designer though I am largely self taught. In my 20s I decided I wanted to be part of making technology better for people and a graduate study in interaction design seemed the best way to do so. I realised quickly the interplay of visual design with digital design and began immersing myself in visual design practice.

The first attempts were really bad. And it was difficult to articulate why: my professors would say things like not enough subtlety and I would work towards subtlety.

Donis A. Dondis’ book, A Primer of Visual Literacy, put into context these practices I learned over time. I wish I had discovered it earlier in my career. But there was some joy in reading it after. What I learned through experimentation was sort of codified.

Arts and Crafts: The Impossibility of Producing Art Without Craftsmanship

As Dondis points out, creative endeavors are subject to judgment based on their degree of utilitarianism; in philosophy, art is not seen as providing “knowldege, historical, scientific or philosophical”, in the words of Kant, however can be a sort of truth because “it makes us more aware of our mental activity.” This is not necessarily true of utilitarian art, which may have beauty, but first must address the practical purpose (can this vase hold water?), and also the commercial purpose (will someone buy it?). It is degree of subjectivity and objectivity: a painter may create for herself based on what she determines to be beautiful (subjective), but the commercial artist moves into the objective sphere (Dondis uses an airplane designer as an example, who is restricted in using “the assembled shapes, proportions and materials [that] will, in fact, really fly”).

This is often culturally defined, depending on historical moment.

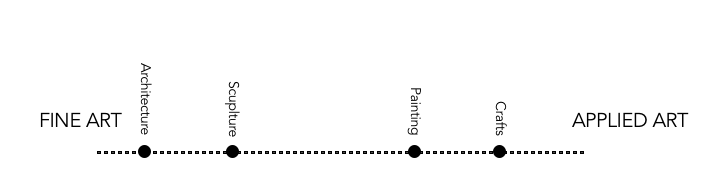

While the Pre-Renaissance made a wide distinction among broad groups

In the Pre-Renaissance, Fewer Types of Design, Keenly Separated Between Applie and Fine Art

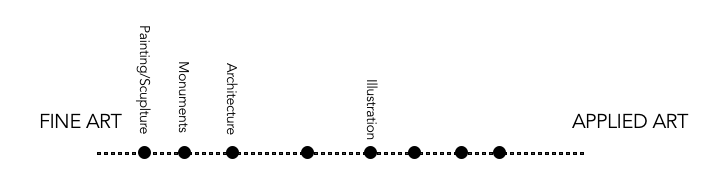

In the time of Dondis’ book (1973), there were more distinct categories, equally spaced out.

In the 20th Century, The Types of Design are More Varied, But Still a Clear Delineation

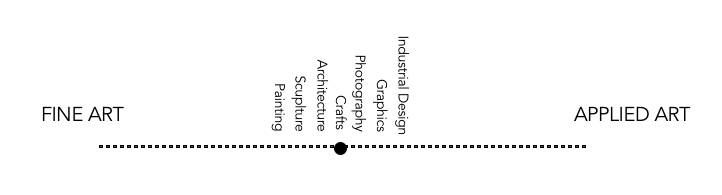

Today, as technology is so integrated into daily life, and the commercial aspires to the artistic (a very convincing car commercial assures us that their car seats are designed by skilled artists), we likely would place our modern era in the Bauhaus timeline, which “would group and all of the fine and applied arts on one central point in the continuum”.

In the 21st Century, as in the Bauhaus, Design is Seen as Artistic, Artistic as Design, in a Narrow Specturm

This is why UX Designers are often called to be visual designers; there is some sense that visual design, or aesthetics, is not separate from creating something functional. The arguments of whether UX designers should code, or be visual designers, fall away when one works as a UX designer..the idea that you could not do one of these things makes you less of a craftsperson; we’ve embraced the Bauhaus and Arts and Crafts spirit. This means visual literacy is essential, or at least the recognition of it as a skill to be developed.

What is Visual Literacy

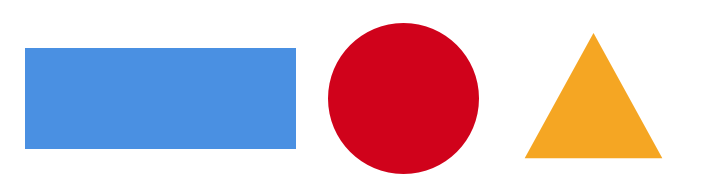

Design is About Decision-Making; Limits Can Be Inspiring, Even if You Must Only Use Three Shapes

Many experiences in studying Human Computer Interaction and Interaction design stick with me; but two in particular stand out.

The first was in an advanced HCI course at Drexel University; our professor one day presented us with two options for an in-class exercise: use a blank piece of paper and design anything we want; or, be restricted to using three business conditions to design something.

In one respect, the blank paper was appealing, which is why my group chose it: it’s blankness meant it could be anything we wanted it to be. This, however, presented a problem: where do we start? This took up a large amount of our time; as we debated, we looked over at the other group, who were already designing interfaces.

Of course, having restrictions allowed the other group to define the problem space, and, hence, the aided in the design process. For, design is about decision-making, and visual design in UX is about how a multitude of decisions will impact user perception, feelings while using the product, and how the product will be used.

As Dondis writes, “we create a design out of many colors and shapes and textures and tones and relative proportions; we relate these elements interactively; we intend meaning.” This meaning becomes the basis for our composition.

A lot of how we experience visual experiences (and life, for that, matter), can be described by Gestalt psychology. In visual design, the use of specific elements together “modify space and arrange or derange balance…create the perception of a design or an environment or a thing.” In life, this can be problematic to achieve: we can focus on a problem without seeing the larger picture (one negative person, for instance, can make it seem like the overwhelmingly larger number of kind people are not really there).

This is the problem of design, creating the right perception. Dondis provides rules for this that read like the work of Don Norman, or the Material design manual, or any other usability writing. Dondis was prescient about the importance of thinking this way in commercial design; he emphasizes media, but is focused on photography, the ability to create images instantly. His main argument for the need for visual literacy is that with this increased ability to create the visual, and share it with the world, we would all be better off understanding what creating something visual means to the people who will view it. When he writes about our visual preference for the lower left, we can’t help but think of all the writing and thought that has gone into where to place call to action buttons in interfaces, all based on ideas of human perception.

The most wonderful thing about Dondis’ book are the illustrations and exercises, which serve as entries into visual thinking. Juxtaposing designs, showing how arrangement of shapes can evoke feelings of peacefulness or violence, indicating that we can represent something symbolically (what user interfaces rely on) or representationally, makes one a better designer.

When I first shared a briefer review of this book, one person I knew said, the book sounds interesting, but isn’t visual design largely intuitive? It was a good question; Dondis’ book seems to imply at first that anyone can become a better designer, but he also recognizes inate skill.

Honing Visual Literacy

“There is a Berlitz approach to visual communication,” Dondis writes,

“You don’t have to decline verbs or spell words or learn syntax. You learn by doing. In the visual mode you pick up a pencil or crayon and you draw.”

This is a hopeful message, but soon after Dondis writes about a difference between designing based on an understanding of visual principles, and designing because one has natural ability.

This is the idea that design is largely intuition; this may seem bad news to those who want to be better at visual design, but, as Dondis points out, it also presents a problem for those who seem to have it. Intuition is often defined as “immediate apprehension or cognition” and “quick and ready insight.” As Dondis writes, the association of intuition with visual design “makes it all to easy to be taken seriously intellectually. And the artist is unjustly stripped of his special genius.”

I mentioned my first most memorable design school experience; my second was memorable for its sheer truthfulness. As the group of us walked into class one day, the professor had one slide showing on the screen.

Not Safe for Some Work, But Safe for Design Work. Not All Products Are Equal. This Keeps Good Designers Up At Night

The words were (and are) striking, shocking even; the larger point he was making was that a lot of designed products are not good, and that we can (and should) judge their quality (and, consequently, as designers, be judged for what we create).

This means being able to judge some attempts at design as better than others, and to acknowledge skill; if all design is intuition, how does one begin to clearly state why one effort is better than another, without a response that this judgment is subjective and just an opinion?

The point of Dondis’ book is to provide design, particularly commercial design, a basis in intellectualism. However, he also truly believes we all can become better at it. The idea that we have internal qualities that always be heightened or improved is inspiring; it’s what made Bob Ross and Julia Child such cultural icons: even if we never painted happy little trees along with Ross, or followed Julia along in our kitchen, it gives us a sense that these activities are not cut off from us because we do not have a “natural gift”.

When I worked for the School of Visual arts, my co-worker was an artist; I proudly showed her a book I bought on drawing. She insisted I throw it out, and just practice drawing, draw over and over again. There was some sense to this argument, and after designing things across years (first in graduate school, then in work), I can attest this practice has made me better. However, reading books like A primer of visual literacy are helpful in reifying practices, of helping you when you do practice. Design is hard, and requires you to be many different people: it encompasses visual decision-making, getting organizational buy-in for a concept or direction, and thinking about (or even doing) the construction. All of these are skills to be developed over time. Which is why books like A primer of Visual Literacy are like good medicine.